Body Positivity: Paradigm Shift or Social Media Trend?

A Northeastern University School of Journalism Honors in the Discipline Special Report

By: Hope Broadhurst

The Debatable Impact of Body Positivity Online

Siera Qosaj, a first-year Northeastern student, struggled with anorexia off and on throughout her teenage years.

“Tumblr was–if it wasn’t the sole reason, it was definitely the catalyst,” she confessed.

Qosaj grew up hearing the women in her life bemoaning their own bodies, which she assumes influenced her developing body image. But the effect of that subliminal messaging did not compare to the social media culture she was immersed in. Qosaj’s feed was filled with black and white photos of Kate Moss and girls with “like, really thin thighs.” This messaging was explicit, teaching Qosaj that extreme thinness was desirable, cool and worth any cost.

When Tumblr was phased out of the popular imagination, Instagram easily replaced Qosaj’s source of “thinspiration” – photos meant to remind those with anorexia why the restriction is worth it. She still has the folder on her phone, a collection of thin bodies gathered on various social media which she would scroll through as she lay in bed late at night, crying.

That was around the time body positivity was reaching its mainstream peak, in the late 2010s and early 2020s. Unlike anything that came before, it promoted self-acceptance, self-love and self-confidence, regardless of how your body appeared. It was a radical idea, born from the fat activists of the ‘60s. It has since shaped media campaigns, company rebrands and the politically correct lexicon of the youth. But didn’t protect Qosaj.

Rachel Rodgers specializes in body image research as an applied psychology professor at Northeastern University. “Things get introduced as a form of resistance and then they get co-opted,” she explained. Ultimately, “you can’t have a widespread, mainstream movement of resistance.” While body positivity has been a life-saving message for some, it was enveloped by a wider culture that openly values some bodies over others. The contradiction was destabilizing to the mission of inclusion.

Young, blond influencers with perpetually glowing faces and plump lips sell enumerable wellness practices while vlogging early morning Pilates classes. Their posts are tagged “body positive” because the obsessive regimes, the green juices and the restraint are all in the name of self-care.

Jacked, “alpha men,” broadcast the vicious cycle of intentional weight gain and loss which most rapidly grows their muscles–bulk, cut, bulk, cut. To them, being accused of steroid use is a compliment. Their posts are tagged “body positive” because constantly being better, stronger, bigger is real self-love.

Even thinspiration–content which promotes and encourages eating disorders–can be hidden under the guise of body positivity. After all, loving their thigh gap is loving their body, right?

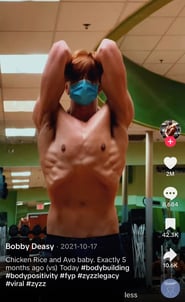

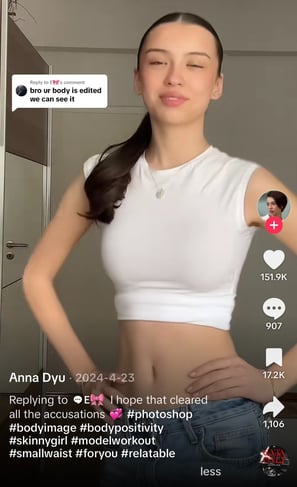

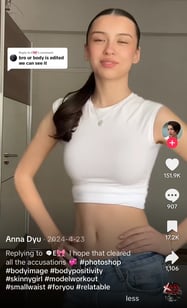

TikTok user Bobby Deasy [left and center] posted a video revealing his extreme, 5-month transformation, eliminating the majority of fat on his body and “getting shredded.” Influencer Anna Dyu [right] responded to accusations that she edited her body with a video proving to her audience that she really is that thin. Both are tagged #bodypositivity. (Source: @bobbydeasy, @anna.dyu)

Jennifer Harriger, Ph.D, is a professor of psychology at Pepperdine University whose research focuses on the relationship between social media and body image. In 2023, she co-authored an analysis of body positive content on Tik Tok. According to that research, only 32% of videos tagged body positive involved plus-sized people and only 32.2% of videos contained messaging aligned with body positivity. “A lot of the people in the videos had very idealized appearances,” Harriger said. “They were thin, young, conventionally attractive white women.”

Decreasing the exclusiveness of beauty – and the benefits that come along with being beautiful – is not a proposition that has aligned with the materialistic, appearance-obsessed, highly competitive nature of the modern social media landscape. As the body positivity movement grew and its influence swelled, it became a hollowed-out version of itself. What was once a space for people whose bodies had been marginalized became an open floor for whomever could manipulate the messaging for the most attention.

“I think the social media approach of people that look like me, leveraging [body positivity] as their own liberation, is really missing the mark,” said Abbey Griffith, owner of Georgia’s first body positive gym, Clarity Fitness. She was first exposed to body positivity during eating disorder therapy, where, “in some regards, it was really, really helpful.” They were the conversations she needed at the time, conversations about embracing her body at all shapes, sizes and abilities.

But the more she learned, the more reservations she had. Griffith has immersed herself in more radical spaces and stepped back from her initial understanding of body positivity. To her, the root of movement -- “recognizing that every body has a place at the table,” is an essential message. But online body positivity isn’t representative of the “weight-inclusive” and “eating disorder-informed" space she is crafting. Since Clarity Fitness opened in 2020, Griffith’s commitment to the term has dwindled. It was chosen because it easily communicated the “gist” of the gym’s brand, but Griffith was quick to clarify, “We definitely are aware of the issues of using that verbiage.”

Molly Robson, an independent therapist specializing in body-image issues and disordered eating based in Roslindale, Massachusetts, has also been disappointed in body positivity. She grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, immersed in extreme diet culture. Like Griffith, the foundational ideas of body positivity informed her healing, as she unlearned the unforgiving expectations she had for her body. Also like Griffith, “I think the original meaning has gotten lost in social media.” she said of body positivity. “I think it used to mean a lot more.” Now, Robson feels that it can be counterproductive, erasing the “spectrum of normal human emotions... that everyone experiences.” Body positivity doesn't represent something she wants for herself or for her clients anymore.

Ultimately, body positivity hasn’t been able to keep up with deep-rooted biases against fatness. Harvard’s infamous Implicit Associations Test (IAT) attempts to measure the negative and positive associations people have with certain populations. With 4.4 million tests taken over 13 years, a comparative analysis done in 2016 looked for long-term patterns. Implicit bias decreased in every single other category – against diverse sexualities, races, ages and disabilities – but weight-based implicit bias increased.

Mattel’s body diverse Barbies, released in 2016, included petite [far left], tall [middle left] and “curvy” [middle right] dolls. Body image researcher and psychologist Jennifer Harriger, Ph.D., found that young girls “were clearly biased in favor of the thinnest bodies,” in a 2019 study. (Source: New York Times)

Other research corroborates the movement’s failure to take hold. In 2016, Mattel released a line of body diverse Barbies. Harriger, the Pepperdine University body image psychologist, contacted the company, curious about how the dolls were received. Her requests for sales information were denied. Committed to understanding the impact of the toy, Harriger designed a study of her own in 2019, assessing how girls aged 3 to 10 interacted with it.

“We found that kids were less likely to want to play with the curvy Barbie doll, who really was maybe a U.S. size 4 to 6,” Harriger revealed. “We’re not even talking plus size. This was lower than the average size in the United States.” The kids attributed more negative characteristics to the curvy Barbie doll compared to the other dolls in the study, most likely to identify her as the one without friends and least likely to identify her as smart, pretty or happy. At least 25 percent said they would not want to play with her because she was “fat, cubby or big.”

The implicit bias tests underscore people’s difficulty associating positive traits with fat bodies. Harriger’s study reveals that this correlation between body-size and worthiness has been passed on to children as young as 3.

Popular culture values thinness beyond its perceived aesthetic merit. Thinness is seen as the prerequisite to wellness, happiness, intelligence and respect. “Thinness is shorthand for everything else good,” offered Cornell lecturer and expert in the culture of American food and health, Adrienne Bitar, Ph.D.

If number of hashtags is a meaningful metric, body positivity certainly made its mark on the culture. But as the explicit thin-supremacy and fat phobia begin to re-emerge (from their implicit hiding spots), the sincerity and longevity of that shift remain hotly debated.

Bitar, author of the 2018 “Diet and the Disease of Civilization,” said the peak of the diet industry is today. It’s every day.

“It’s just this ugly beast that comes in so many different costumes,” she insisted. “You can say all this euphemistic BS, but it’s all the same stuff. I think people are more coy about it now. And the body positivity movement and the fat activism movement, the health at every size movement are all well-meaning. But it’s not like anything changed, actually.”

The History of Thinness as a Virtue

The last 60 years of American culture largely encompass the universalization of thinness as a virtue as well as burgeoning resistance against fat-phobia. However, thin supremacy can be traced back centuries, influenced by racism and misogyny in ways this article won’t explore.

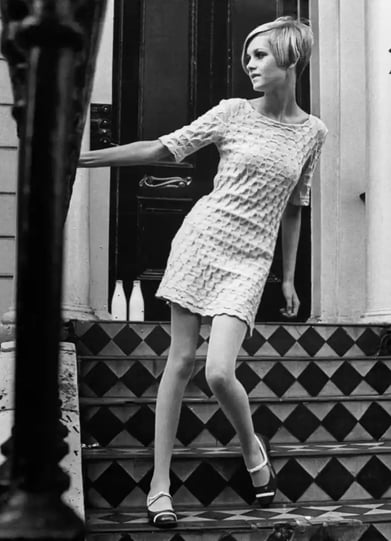

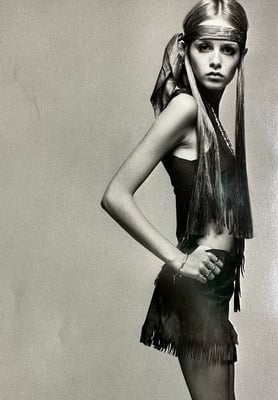

In the 1960s, thin was officially, irreversibly in. The flapper girls of the 1920s had been a taste, but years of war and recovery put the ideal on hold. When rationing and limited supplies were the norm, excess weight was a sign of health and resources. Once the dust had settled and average Americans once again had access to surplus calories, self-control became the trait in vogue. Androgynous, slender figures emerged as the paragon of beauty. Twiggy, the teenage British model with exceptionally thin arms and legs, was the face of the culture.

Lesley Hornby, known globally as Twiggy, was the paragon of beauty and fashion in the ‘60s. (Source: Woman’s World [left], Worcester News [right])

Billions of “rainbow” diet pills were being sold every year to consumers willing to do anything, take anything, in the pursuit of thinness. As the death toll from these concoctions mounted, a LIFE Magazine reporter who weighed 130 pounds visited “fat doctors” to see what they were willing to prescribe when it was medically unnecessary. Susanna McBee, the journalist, was given 1,479 pills across 10 visits. Of one, she recounted, “I asked what was in the pills. He did not tell me but said only that the pinks would suppress the appetite, the browns would keep me from being constipated… and the others would work with the pink to reduce me. They contained, it turned out, amphetamines, laxatives and thyroid.”

Unlike modern diets, health was rarely the central focus in the ‘60s. Rather, diets promised to release people from the shame and isolation of being fat.

Jean Nidetch, a Queens, New York, housewife with a history of yo-yo dieting, had a dream: “a slim figure with the youthfulness, vigor and personal happiness which it promised.” She founded Weight Watchers in 1963 after, at long last, she landed on a sustainable weight loss plan. Nidetch insisted that others could also escape the social prison of fatness if they followed in her footsteps.

This was a selling point for Weight Watchers, and many other weight-loss plans – the promise of acceptance. The mockery and exclusion of fat people was natural and unquestioned.

The first major sign of resistance was in 1967, when 500 people gathered in Central Park for a “fat-in.” They carried signs, sang, ate, burned pictures of Twiggy and diet books and shamelessly took up space.

Later that year, an article entitled “More People Should Be FAT,” was published in the Saturday Evening Post. Lew Louderback, the author, described the relentless stigma he, his fat wife and every fat person in America faced. “Most Americans, being devotees and victims of the slimness cult, do not care when fat people are subjected to persecution,” he declared. He referenced a Harvard study that showed definitive discrimination against fat people, who were significantly less likely to be accepted by college interviewers.

Louderback’s article was discovered by Bill Fabrey, who was dissatisfied with the world’s mistreatment of his fat wife. Inspired, Fabrey passed the piece around to everyone he knew and eventually connected with Louderback to create what is now known as the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA). It was abundantly clear to a small group of radical thinkers that fat people were oppressed, and popular culture was unwilling to acknowledge it. This was the foundation of fat acceptance, a movement that pushed for the recognition and correction of the abuse of fat people.

In the early ‘70s, the Fat Underground branched off from NAAFA as an extremist sect that included more outspoken feminists, activists and lesbians. For this group, fat acceptance wasn’t enough. Fat liberation was the goal. In 1973 they released their “Fat Liberation Manifesto,” which began, “We believe that fat people are fully entitled to human respect and recognition.”

In 1982, Jane Fonda’s first home workout video was released. Fonda epitomized the shifting beauty standards—bigger hair, smaller waists, more athletic, still thin. Between 1982 and 1995, 17 million copies of the series were sold. “Feel the burn,” Fonda would tell her audience, wearing her signature leg warmers, captivating them with her toned body and the implication that it could be theirs if they followed along.

Fonda, now 87, has since revealed that this era of her life, from her 20s to her 40s, was defined by a crippling eating disorder. The standard of what a healthy woman looked like was someone on the brink of slow suicide by starvation.

Jane Fonda epitomized beauty standards of the ‘80s and brought aerobic exercise into the homes of millions. (Source: Air Mail)

Fat activism was niche, but it began appearing more publicly. Judith Stein was a founding member of the Boston area fat liberation movement. She gave an impassioned speech at a 1986 pride celebration detailing the severe consequences of fatphobia: “Fat people are still the butt of jokes but fat oppression is no laughing matter. Fat oppression kills fat people. It kills us through repeated diets which fail 98% of the time and leave us weak and sick. It kills us through surgeries which cut or rearrange our intestines or stomach and can leave 10% of us dead on the operating table. But most often fat oppression kills us slowly, through constant harassment by strangers on the street and our friends and lovers telling us that we are just not good enough as we are.”

For most women in America, though, the ‘90s brought a glamorization of thinness so intense that the ideal was quite literally skeletal. A teenage Kate Moss had her breakout moment in a Calvin Klein ad and became a symbol of “heroin chic.” The controversial new aesthetic was born from grungy magazines portraying exposed, sickly and incredibly thin female models.

Kate Moss became the face of “heroin chic” after her 1993 Calvin Klein ad. She was a controversial figure, accused of promoting eating disorders and drug use by parents and politicians. In the mid 2000s she popularized the phrase “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” (Source: Calvin Klein)

In 1996, The Body Positive Organization formed, coining the term for the first time. It was a non-profit inspired by fat acceptance but tailored to eating disorder recovery. This was the beginning of the movement’s shifting lens, from correcting external discrimination to correcting negative self-talk.

The early 2000s initially brought little relief. Kate Moss, still in the public eye, infamously said “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels,” which was then printed on fridge magnets and bathroom scales en masse. Brittney Spears’ 2007 VMA performance was met with unbridled fat-shaming. Reality TV shows like the “Biggest Loser” mocked and tortured fat people while gaining millions of avid viewers.

The 2010s were, in some ways, an obvious continuation of what came before. In other ways, they ushered in a revolutionary new period.

Image-based sharing platforms like Instagram and Tumblr meant that anyone could gain exposure without passing through the gatekeepers of institutional media. At the outset of the decade, body positivity was becoming mainstream, promoted by mostly fat bloggers.

At the same time, thinspiration and communities of anorexic young girls promoting each other’s disordered behavior became widespread.

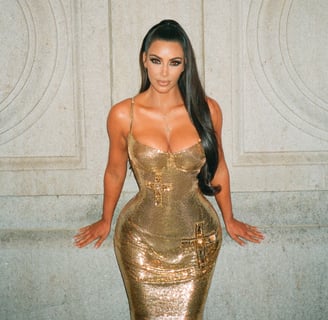

During this time, voluptuous curves were briefly idolized by the mainstream, although thinness was never “out.” The BBL or Brazilian butt lift, which removed fat from women’s stomachs and injected it into their butts, became an iconic procedure. Kim Kardashian and Nicki Minaj, highly influential women of the decade, were known for their shocking waist to hip ratios.

The 2010s introduced the new, equally unrealistic ideal of extreme curves. Kim Kardashain [left] and Nikki Minaj [right] surgically altered their bodies to create and meet the new standard. (Source: Vogue [left], @nickiminaj Instagram [right])

But the change remained narrow, benefiting a small group of people who still checked off unrealistic boxes. “There’s a lot of talk over the past decade or so about how the Kardashians were changing the ideal body,” Harriger offered. “It wasn’t super thin anymore, but everything else that they were promoting is still very unattainable.”

Rodgers, who concentrates on the socio-cultural influences of body image, argues that globalization in conjunction with image-based tools have made appearance ideals more stringent than ever. The social possibility of being desirable has increased, as has the competition. Simultaneously, over the past few years, thinness has crept back to its spot atop the cultural hierarchy. Rogers explained that it is symbolically associated with personality traits like self-control and discipline, “and those things are in.”

But now, “it’s not just thinness,” Rogers argued. “It’s definitely thinness, but it’s a more extreme thinness in the context of all the other stuff. The long limbs, the shiny hair, the golden skin. It just wasn’t quite as onerous in the ‘60s.”

Liberation is Still Possible – and Advisable:

Toni PNW was raised as a transracial adoptee in a conservative Mormon town in southern Utah. “Fatness was treated as something you just tried to get rid of. It wasn’t something people really talked to you about. It was just known that you couldn’t be fat. And you shouldn’t be fat,” she recalled. “I was left out of a lot of things. I was bullied out of a lot of things. I was treated as something people didn’t even want to be seen with. As an object rather than a person.”

The isolation of being a queer, fat, woman of color was crushing. She constantly tried to perform, to be good enough, and she only ever got hurt.

PNW, now 25, got her first taste of freedom when she saw other fat people enjoying their lives. She still remembers travelling with her family outside their tiny town and seeing fat people in tiny outfits, beautiful and unabashed. “First of all, I was gay,” she joked. “And second of all, it was just really exciting to see fat people that weren’t hiding their entire bodies in oversized t-shirts.”

She’s come a long way since then. Living in Vancouver, Washington, PNW is now an inclusive tattoo artist and fat activist. People come to her for her art – apologizing for the inconvenience of their stretch marks and body fat – and she gets to offer them appreciation, understanding and safety. She has also crafted an online community that meets her with support and kindness. “Curating my life for body love and compassion has brought me more joy than I could ever hope,” she said.

Toni PNW is an inclusive tattoo artist and fat activist in Vancouver, Washington. She grew up in a conservative Mormon town in southern Utah, deeply ashamed of her body. She has since found liberation through diverse experiences and communities. (Source: Toni PNW)

This was no easy task. Her shame didn’t just come from inside, it came from all around her. Anti-fatness was ingrained in her hometown, which excluded and rejected her. It was ingrained in her loved ones, who thought that teaching her to conform would protect her. It is ingrained in the functions of society, which disenfranchise bigger bodies at every turn.

According to a 2010 study in the Journal of Applied Psychology: “Heavy women earned $9,000 less than their average-weight counterparts; very heavy women earned $19,000 less. Very thin women on the other hand earned $22,000 more than those who were merely average.”

Research shows that doctors spend less time with, build less report with and carry negative character judgments towards obese patients. Even health professional specializing in obesity “significantly endorsed” the stereotypes of fat people as “lazy, stupid and worthless.”

A Brigham Young University study in 2019 found that fat victims of rape were significantly less likely to be believed than thin victims.

With this tangible, external discrimination in mind, PNW has complicated feelings about modern online body positivity. To her, it is a watered-down version of fat acceptance, which actively rebelled against the injustice of weight biases. When she sees body positivity hashtags, it’s often in conjunction with the thin, Eurocentric bodies featured in “every single advertisement since we were born.” But she also finds that body positivity is an undeniably valuable message.

“Of course everyone should love themselves,” she insisted. “Everyone should enjoy the body that they’re in. It’s when you start putting conditions and barriers and moving the goalpost of who’s allowed to have body positivity that it’s a problem.”

The research shows that Instagram and TikTok content promoting self acceptance is, to some degree, beneficial, particularly in contrast to explicitly harmful alternatives. “It can certainly be protective to a point,” Harriger said. “If people are going to be on social media and they’re going to be exposed to these negative messages, then the more that we can also expose them to positive messages, I think the better.”

Rodgers agreed. “I do think some of the content on social media is helpful,” she said. “Compared to the mainstream content, people definitely feel better about their bodies if they’re looking at body-positive stuff or intuitive eating-related content. That’s a lot of content that’s just humorous and funny and makes people feel like they’re not alone.”

But image-based content, by its very nature, also reinforces the economic and social value of peoples’ appearances. Influencers, who now make up around 3% of the U.S. population, are rewarded for looking “perfect,” passing on the message that conventional beauty is a value-system worth investing in. According to Rodgers, the core of negative body image comes from believing that “you are not as effective as you could be.” Social media validates that. People can make more money by being more beautiful.

The rapid rise of highly successful weight-loss drugs – GLP1s, like Ozempic, which were originally used to treat diabetes – also threw a wrench in widespread self-acceptance. Celebrities and influencers who touted body positivity, insisting that their bodies were beautiful, worthy and healthy no matter what the media said, have begun shrinking, disappearing before our eyes.

The weight loss drugs are “very alluring,” to many of Robson’s clients, who come to the specialized therapist seeking resolution for decades of body-image issues. She is disappointed, although not surprised, by the cultural response to GLP1s – the idea that “if everyone takes these drugs, we won’t have fat people anymore.”

Advertisements for new, highly effective weight loss injections appeared in New York City’s subway stations in 2023. Ro, a company supplying GLP-1s, put up 1,000 ads across 100 stations, according to Bloomberg. (Source: Ro)

When it comes to finding self-acceptance, the academic experts and the personally experienced recommend going beyond pop culture and instead, turning inwards. The truth is that there are benefits to being thin. But they are simply not worth constant inner turmoil.

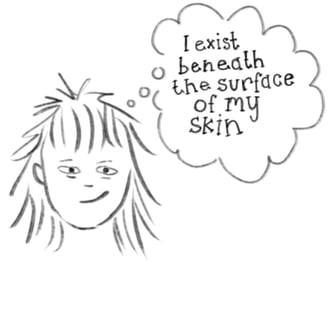

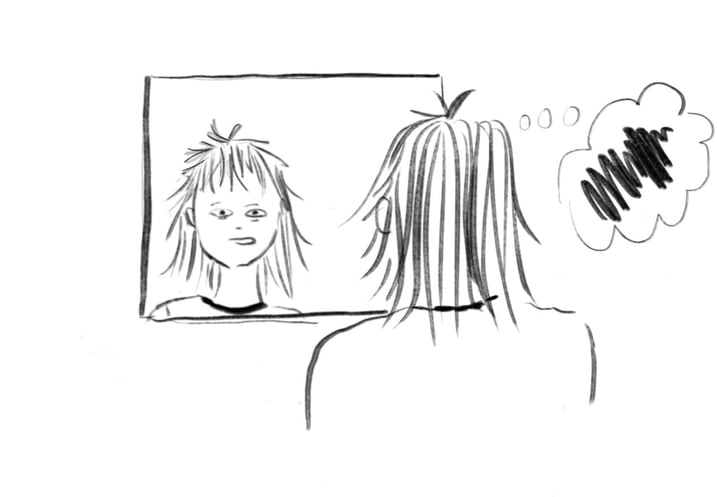

“We can sort of engage in diet culture and engage in pursuing thinness. There’s safety in that,” acknowledged Robson. “I know that’s true, and I still want liberation for you,” she tells her clients. More than anything, more than feeling beautiful, she wants them to believe that “I am a person who exists beneath the surface of my skin.”

PNW feels this nuance acutely. “People really, really do internalize all the propaganda they’re given,” she acknowledged. “I can be so far on my journey… and want differently so bad for people that I love, but they are just trying to survive. They’re trying to survive constantly being told that ‘your body isn’t good enough.’ Constantly being told ‘the way you exist isn’t good enough and people don’t want to see you and you’re not allowed to this and you’re not allowed to that.’” As much as she wants to convince her mother, and every woman like her, that things can be different, the idea that their social value is defined by their appearance is felt too deeply, held too close.

“Yes, it’s probably true that the world would respond to me differently if I looked like a supermodel,” Rodgers argued. “But would that actually make my life better or would I then start to worry that people don’t actually like me because of me, they just like me because of the way I look?”

Celine Lebouef, Ph.D., is a philosophy professor at Florida State University with a particular interest in embodiment. She agreed that, given the conditions of society, wanting to pursue thinness is natural and normal. “So the question has to be, what collectively can we do so that the norm doesn’t prey on people.”

To her, people’s bodies are their point of view on the world: They are multi-faceted, they allow for relationships and experiences and they are not objects obliged to be beautiful. Focusing on whether bodies “[live] up to certain standards is neglecting the whole part of what makes us human,” she argued. “We need to embrace the functionality, the body as a source of pleasure.”

For all the complexities of modern body image – tainted by constant visual access to the “ideal,” as well as the drugs to get there – the escape is rather simple. Fretting over appearances is trained at a young age and validated through experiences. But appearances are just that, a performative veil of identity, unrepresentative of life, love and experiences. Our bodies are not who we are and how other people respond to our bodies is not a reflection of who we are. Staking our worth in them is one option, but it’s not the only option.

PNW took a different path, valuing the magnificence of her unique life for what it was, not what people perceived it to be. She was sick of hiding and she has no regrets. “I love my body,” she said easily and proudly, after years of internal work and community building. “I love how it moves. I love the experiences we’ve had together. I love to see myself growing into my mom and my grandma as I get older. And I’m excited to keep showing that there’s a way to be joyful and not be burdened by body shame.”